Emperor Penguin Expedition

This article originally appeared on dpreview.com.

Penguins are a staple of nature photography these days and one can easily book a cruise to Antarctica for themselves through numerous operators, but that wasn’t always the case. There was a time when emperor penguins were rarely, if ever, photographed in the wild. With this in mind, I invested $25,000 in trip arrangements (a massive investment and an enormous risk at that point in my career).

Essentially I was rolling all the dice at once that I could pull a shoot off. These arrangements put me on my first exploratory photography trip to find emperor penguins on the frozen Weddell Sea in Antarctica. As I said, the penguins had been photographed before, usually as odd members straying towards a base by over-wintering biologists, but I was attempting to photograph them on purpose and I had just two weeks to do it in the Antarctic summer.

The expense of trip was split between me, two explorers, Shirley Metz and Peter Harrison, as well as a French and German photographer—five of us total. We all met in Punta Arenas, Chile, the southernmost city on earth which sounds like a potential paradise. Well, it’s not. We were stuck for eleven days waiting for a break in the weather to allow us to make the trip to Antarctica. During those eleven months of waiting (okay it was eleven days, but it felt like eleven months!), we had no idea if we would even ever see the sea ice or ever travel any further south than we had come.

I was bored out of my mind. To know me is to know I don’t sit still very well. I would have been the poster child for ADHD if it had been diagnosed during my childhood. I memorized every back street and alleyway in the city, not to say that was very difficult as to even call it a city was pretty generous. I visited the one museum four times. The displays never changed, and I ate in every restaurant more than once and the food never improved. My roommate for this internment was a French fashion photographer who had a penchant for smoking the nastiest cigars. Needless to say we had more than one less-than-civil discussion about smoking in our tiny shared accommodations.

Getting underway

On the twelfth day the weather finally cleared and we, perhaps a little too optimistically, boarded an old, rickety, DC6 that looked like it was a set prop for a disaster film. (This plane has since crashed and is today entombed in the Antarctic ice.) Boarding the plane and buckling in all five of us put our faith, and lives, in the hands of the pilots. This was not the time to look for alternative flights, not that we had any choice in the matter.

We soon crossed over the alps of southern Chile and lost sight of land, and all hope, as we crossed the ocean perpendicular to some of the most severe wind patterns on the planet. Sailors know these winds as the Roaring Forties, an area where the winds can circumnavigate the globe over the ocean without ever running into a stretch of land or mountain to slow them down. In hindsight this was perhaps not the best aircraft for this journey. During the entire crossing the plane sounded as if it might fall apart, rattling and creaking, snapping and popping from the stresses on the wings and fuselage. It was not a flight for the faint of heart and just about all of us had found religion of some sort before it was over.

With tremendous relief we descended and eventually lined up to land at the base of the Ellsworth Mountains where the winds are so horrendous as they constantly blew the snow off the ice before it could build up, leaving what is called a “blue ice” runway—hard as cement, but not nearly as smooth. You couldn’t put skis on a plane that size to land in deep snow so this was our only option to get on to the Antarctic continent. With the constant winds the landing was so hard it broke the seats loose from their bolts and the toilet from the back of the plane passed by me where I was strapped in. Perhaps it sensed how badly I needed it just about then?

Arrival at Patriot Hills Camp

First shaken then stirred, once down, the next challenge was to stop the plane before the winds literally blew us back toward the sea. Watching through the small, round, windows I could see it took at least ten people on the ground with ropes to lasso the wings as the winds spun the craft around on the ice and none of us could attempt to stand up, much less deplane (abandon ship was more like it!) until it had been completely arrested. All that said, to this day, I still count the eleven days in Punta Arenas as the worst part of the trip.

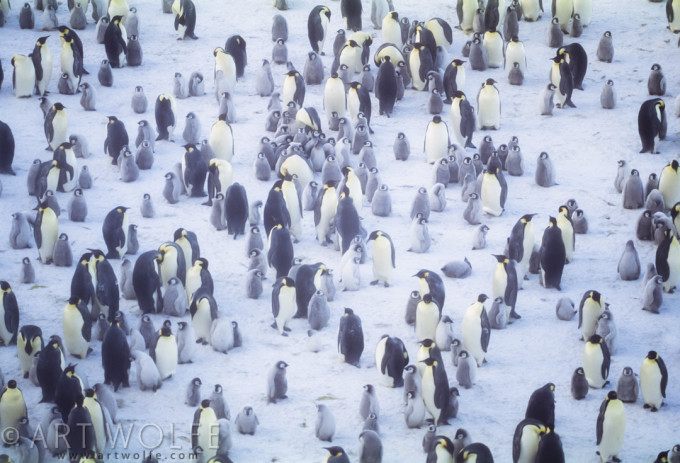

We overnighted in the Patriot Hills Camp from which expeditions traditionally set out for the South Pole. The following morning, believe it or not, we boarded a smaller airplane, a Twin Otter equipped with skis and capable of landing on the snow and flew out over the frozen Weddell Sea circling the ice below searching for a colony of emperor penguins. With much elation we spotted a colony on the ice and after a closer inspection it proved to be the largest colony of birds I could ever have imagined.

With our goal in sight, bearings taken, we landed on the frozen sea a safe distance away. We unloaded our equipment and bid goodbye to the Twin otter with arrangements to return at the end of our intended stay. We immediately got a visit from a few curious locals; however, the weather turned for the worse and we set up a base camp we were caught in a blizzard that buried us in our tents; we had no choice but to hunker down not knowing how long we might be stuck this time. Oddly enough, Punta Arenas was starting to look better and better.

Waiting for weather

For several days we sat and we waited. We melted snow for water and cooked our freeze dried meals; we traded war stories, told the same jokes, none of us knowing if and when we’d ever get a break to try and find the birds or how the plane might even find its way back to find us.

It was difficult to sleep, the sun never actually setting below the horizon and I found myself awake in the middle of the night wondering what I was hearing, or rather what I wasn’t. It was calm. Aside from the snoring in the nearby tents around me I couldn’t hear a thing. I stuck my head out of the tent to check on the weather and there I could see the sun shining through a break in the clouds at its lowest point in the sky, it was the first I’d seen the sun or any semblance of sky since the blizzards had pinned us down.

Everyone else was completely sound asleep, sacked out solid in their bags and rather than try and wake them and risk missing what could be a fleeting moment, I grabbed my equipment and half ran, half hiked two kilometers across the ice and snow to where I thought we had seen colony from the air.

Foolish? Absolutely. The storm could have returned at any moment, the sun was only breaking through a small gap in the clouds. Had the wind picked up at all I would have immediately turned in my tracks for the tent. I was well aware of the danger. (Several years later a photographer who called himself ‘Mr. Penguin’, Bruno Zehnder, well-versed in photographing in the Antarctic set out as I had, alone in the night, when the weather did pick up. Attempting to return he missed an entire research base by only 50 yards and froze to death.)

I would have been looking for just several small tents. If I had gotten into any kind of trouble, twisted an ankle, broken through the ice, if the storm had come in or even the winds picked up and I got disoriented and lost my tracks I would have been dead. I was fairly well-trained in climbing as I grew up in Washington State climbing the volcanoes of the Cascades. All those skills come right back to you when you are out there reliant on your own wits and strength to see you through.

Close encounters

With a lot of luck and good karma I managed to hike the two kilometers and the penguin colony had obligingly awaited my arrival. For three unbelievably glorious hours at 2:30 in the morning, in the month of November when the sun never sets, I had 10,000 emperor penguins to myself. They were bathed in golden light and the most difficult thing about the whole process was getting photographs without having them coming up to me and pressing their belly feathers into my lens.

They were extremely curious; they wanted so badly to investigate me that I always had to keep moving, walking backwards, ahead of the pack to get portraits of mothers with chicks and fathers with their babies on their feet. That was the whole objective, to get lots of babies in golden light, and I got them! Oh boy did I get the shots!

I found my way back to my tent without incident, welcomed by the snores and sounds of slumber and fell asleep in my down bag with what I’m sure was a giant grin on my face. Hours later I awoke to conversation, breakfast cooking and the sound of the violent storm outside my tent, it was snowing hard. After some teasing for sleeping in I said to them that I had gotten up in the middle of the night and seen the colony. No one believed me.

“Yeah, yeah, right. Tell us another story about how you saw a polar bear too! Ha, ha ha…” Well, we went to bed in a blizzard, woke up in a blizzard, absolutely no tracks to be seen, why would they believe me? As this was 1992, long before digital capture, no one would believe my fantastic tale until we had returned home and I had the film processed and could share the images with them.

That was the one and only break in the weather we saw the entire time on that expedition. We flew back to Punta Arenas in that same decrepit DC6, no one believing my story. For one full calendar year I got those photos on the covers of nature magazines around the world making back my $25,000 dollar investment. Because of those images, the following year Russian ice breakers went down to the Weddell Sea replete with helicopters and many of my top colleagues to photograph the emperor penguins on the sea ice. An entire industry had been born out of my success that night in November, 1992.

What a wonderful story. Simply captivating. And, of course, that last photo is a personal favorite.

You write so well, Art. I could totally feel your boredom in Punta Arenas and the disbelief of your colleagues. The gods were surely with you.

Beautiful story! Thank you for sharing.

You were living in tents? In that kind of weather? Even in such extreme adversity, you were able to film the parents and baby penquin family that you have shown here. My goodness, what a warrior you are. Congratulations. I will search for your website to decide which photo book to buy. God speed, Art. You are so AWESOME !